The World Migratory Bird Day 2025 marks the return of a tagged Eurasian griffon (Gyps fulvus) that has completed an incredible migratory journey of over 6,000 kilometres between India and Kazakhstan. The bird’s extraordinary flight underscores the importance of protecting migratory routes and highlights the value of international cooperation in raptor conservation.

Credit: Pratik Desai/ WWF-India

RESCUE AND REWILDING

In early March 2025, a weak Eurasian griffon was rescued from Satna in Madhya Pradesh and brought to Van Vihar National Park, Bhopal. The bird showed signs of dehydration and poor appetite and was treated with fluids and nutritional supplements. It quickly regained strength, and its recovery further accelerated once it was introduced to other vultures at the Vulture Conservation Breeding Centre in Bhopal, highlighting the social nature of these gregarious birds.

At the end of March, the Madhya Pradesh Forest Department, under the leadership of Mr Aseem Shrivastava, IFS, PCCF (HoFF), and Mr Subharanjan Sen, IFS, PCCF (Wildlife) decided to release the rehabilitated bird back into the wild after observing a number of wild Eurasian griffons near the Halali Dam carcass disposal site. WWF-India joined the efforts and fitted the vulture with a satellite tag to track and monitor its movements.

The bird was released on 29 March 2025, marking the start of a journey that would cross international borders and reveal critical insights into the migratory ecology of raptors.

Credit: WWF-India

Credit: WWF-India

CROSSING THE BORDER THROUGH THE MIGRATORY ROUTE

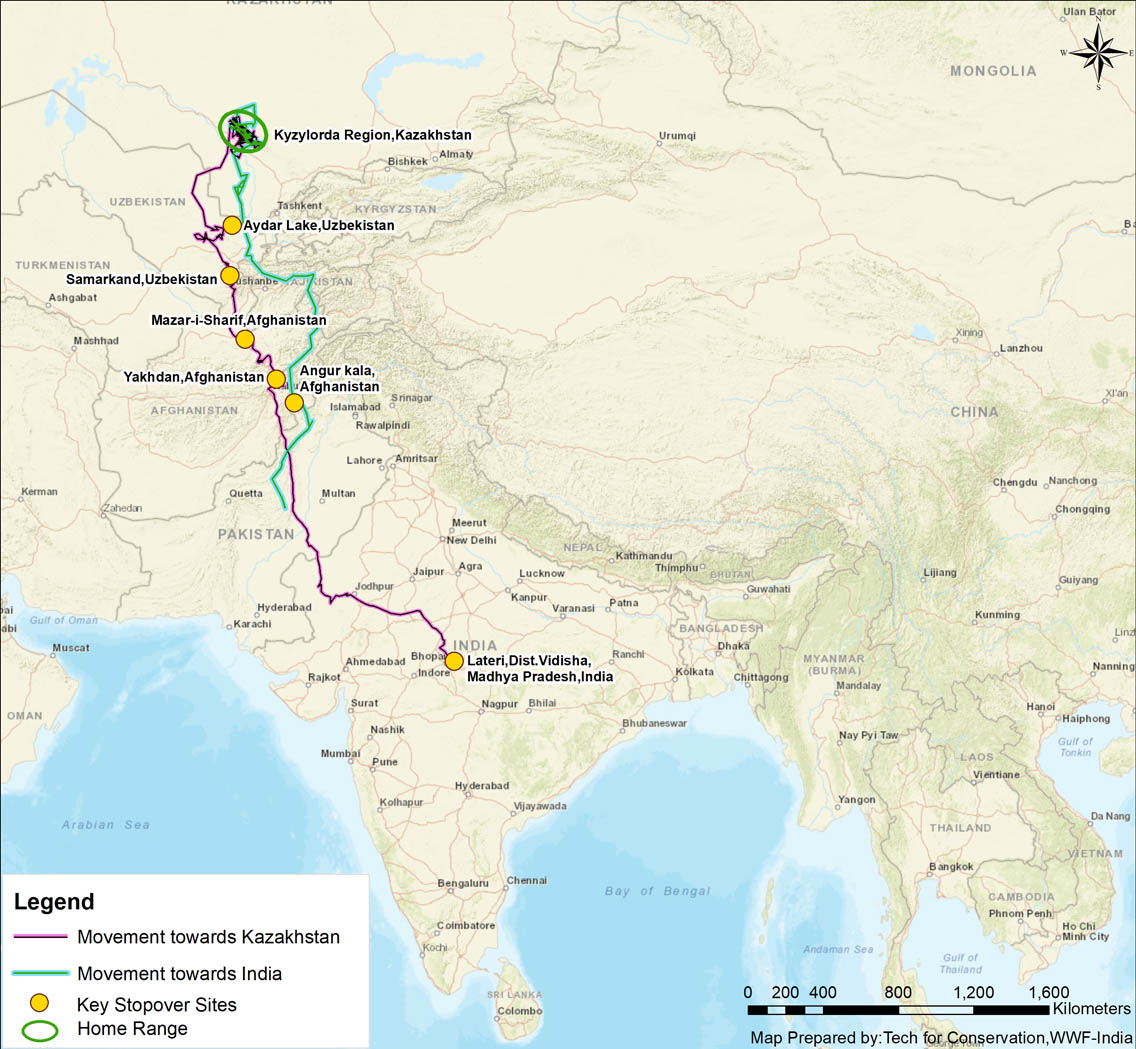

After a brief stop in Madhya Pradesh’s Vidisha district in India, the vulture began its northward journey, crossing Pakistan, Afghanistan, Tajikistan, Uzbekistan, and Kyrgyzstan before reaching Kazakhstan within 44 days, covering an average of 72 km per day. Such movements are typical for Eurasian griffons, which breed in Central Asia and migrate south along the Central Asian Flyway (CAF) to winter in the Indian subcontinent.

During its outward migration, the tagged griffon made brief halts of two to five days at only four locations, namely, near Yakhdan and Mazar-i-Sharif in Afghanistan, a location 22 km from Samarkand in Uzbekistan, and near Aydar Lake in Uzbekistan, before finally settling in the Kyzylorda region in Kazakhstan on 11 May 2025.

RETURN OF THE GRIFFON

Credit: Pratik Desai/ WWF-India

The return journey of the tagged Eurasian griffon has been even more remarkable. As of today, 11 October 2025, the bird is about 250 km from the nearest entry point on India’s border in Jaisalmer district, Rajasthan, and has taken only a single two-day break since leaving its summer range on 23 September 2025. Covering thousands of kilometres in just over two weeks showcases the endurance of these large raptors, which weigh between 8–12 kg and rely on rising air thermals to travel vast distances with minimal effort.

The arrival of the Eurasian griffon also coincides with World Migratory Bird Day, observed globally to highlight the importance of migratory birds and their challenges. This year’s theme, “Shared spaces: Creating bird friendly cities and communities,” emphasises coexistence between people and migratory species. The griffon’s 6,000 km journey reflects this spirit of shared spaces and international cooperation, passing close to cities such as Bhopal and Jodhpur in India, Kabul in Afghanistan, Firoza in Pakistan, Samarkand in Uzbekistan, and Turkistan in Kazakhstan, reminding us that migration connects ecosystems and nations alike.

The timing also coincides with the seasonal arrival of other migratory vultures in India, with sightings increasing along the western border around mid-October.

ECOLOGICAL SIGNIFICANCE OF MIGRATORY VULTURES

Credit: Nikhil John/ WWF-India

Credit: Nikhil John/ WWF-India

Bird migration plays a crucial role in maintaining ecological balance. Migratory birds help pollinate plants, disperse seeds, control pest populations, and connect ecosystems across continents. Of the nine vulture species found in India, the Eurasian griffon and Cinereous vulture (Aegypius monachus) are long distance migrants. Shifts in temperature, food availability, and breeding needs drive their seasonal movements.

The Eurasian griffon breeds in Central Asia and winters in northern and central India, frequenting carcass dumps and open landscapes such as Jorbeed, Bikaner (Rajasthan), one of Asia’s largest congregation sites for migratory vultures. Similarly, the Cinereous vulture, a Near Threatened species, follows a comparable winter migration from Central Asia to India and Pakistan. Even Himalayan vultures (Gyps himalayensis), though mostly resident at high altitudes, make seasonal movements southwards to the Indian plains and Deccan plateau during winter.

These migrations sustain ecological continuity between mountain and plain ecosystems, while the vultures’ scavenging role helps remove carrion and prevent disease spread across regions.

IMPORTANT PITSTOPS - THE LIFELINE OF MIGRATION

Long distance migration demands immense energy, making rest and refuelling essential. Migratory birds rely on stopover sites that are key habitats providing food, water, and safe roosting opportunities. Such sites are often characterised by open terrain, wetlands, grasslands, and river valleys that generate favourable thermal air currents for soaring species like vultures. Stopovers, where birds rest for 24 hours or more, link breeding, wintering, and migratory corridors. Loss or degradation of these sites due to land use change, pollution, or infrastructure development can disrupt migration and increase mortality. Identifying and protecting these sites is critical to maintaining healthy migratory populations along routes such as the Central Asian Flyway (CAF).

CHALLENGES AND CONSERVATION ALONG THE CENTRAL ASIAN FLYWAY

Migratory birds face a range of threats along the Central Asian Flyway, including habitat loss, poisoning, electrocution from power lines, and reduced availability of safe stopovers. A stark reminder of these challenges is the Siberian crane (Grus leucogeranus), whose central population, once migrating from western Siberia to India, has vanished completely, with the last confirmed sighting in Keoladeo National Park, Bharatpur, in 2002. The decline was largely due to hunting and habitat loss along its route through Afghanistan and Pakistan, particularly around key wetlands such as Ab-i-Istada Lake.

This loss underscores how migration cannot recover without coordinated action among countries to secure routes and habitats across borders. The Convention on Migratory Species (CMS) offers a framework for such cooperation. Through the Raptors MoU, countries along the flyway can work together to prevent poisoning, safeguard habitats, reduce collision and electrocution risks, and promote safe veterinary drug use, thus safeguarding migratory raptors. The MoU also fosters telemetry-based monitoring and data sharing platforms to identify priority conservation sites.

Having partnerships among governments, NGOs, communities, and industries across more than 30 range states in South and Central Asia, the Raptors MoU helps integrate raptor conservation into broader frameworks such as One Health and ecosystem resilience, linking wildlife conservation to public health and climate security.

THE JOURNEY CONTINUES

As the tagged Eurasian griffon nears India, its return marks not just the completion of a 6,000 km odyssey, but a shared success for science, conservation, and collaboration. Each tracked journey adds to our understanding of how migratory raptors use space - where they forage, rest, and survive across countries and continents. These insights are important for identifying conservation priorities and ensuring safe passage for raptors along their flyways.

The vulture’s journey is a powerful reminder that the skies connect us all. Migration transcends borders, linking nations through a shared responsibility to protect the species that unite our ecosystems in flight.

Eurasian griffon is widely distributed across Europe, Asia, and North Africa, with strong populations in Spain and France. In India, it is mainly a winter visitor to the northern and western states and the only vulture listed as “Least Concern” on the IUCN Red List, with 80,000-90,000 mature individuals found globally. It thrives in open mountains and plateaus but faces threats such as poisoning, habitat loss, unsafe veterinary drugs, and collisions with power lines.

AUTHORS: Madhya Pradesh Forest Department and WWF-India

Disclaimer for maps:

The maps, where depicted, are not a legal description or a reflection of any expression or opinion or advise of any nature and do not warrant correctness, current situation, limitations and accuracy. The depiction is strictly representational and should not be relied upon. WWF-India shall neither be responsible for any maps being misused or misrepresented by any other third party/ entity nor be responsible for any damages, consequential losses, costs, expenses incurred basis any action/ commission.